“Thoughts without content are void, intuitions without conceptions, blind.” - Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, 1781

We often hear, or at least I have, how there are too many radical ideas these days and not enough middle ground or the center. Commentators on mainstream news say things like, there is radicalism on both sides of political parties and “America’s left and right are radicalizing each other.” Well, for one thing there most certainly is extremism on the right wing of politics these days from book banning to right wing ideology inspired terrorism and mass shootings. None of which can be seen being done on the left.

But while I have your attention, let me bring to your perception a few great American radicals, and by way of writing about them, I hope it can show a bit of praise for what some radicalism can be. But before we get there, lets start with two major eras of world history with some historical context that led up to these people.

The first being the Age of Enlightenment. A revolutionary era of art, philosophy, and science that threw the western world into a new phase of social evolution, arguably beginning in 1637 when René Descartes published Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One's Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences. In the first paragraph of this work he wrote, “The greatest minds, as they are capable of the highest excellences, are open likewise to the greatest aberrations; and those who travel very slowly may yet make far greater progress, provided they keep always to the straight road, than those who, while they run, forsake it.” Also in this time, was the first publication of the Encyclopedia by Denis Diderot and at least 150 other intellectuals, later banned by King Louis XV in 1759.

This new period emerged during historical times of Christian theocracies. The mid 1500’s saw Queen Mary I of England, where in just five years, over 280 religious dissenters were burned at the stake during the Marian persecutions. In the years of 1562 to 1598, the French Wars of Religion took place with estimates between two and four million people dying from violent execution, famine, and diseases. From 1547 to 1575, Ivan Vasilyevich (Ivan the Terrible) under the belief of unlimited power by God, forced the masses of northern Europe to follow a bible of sorts called Domostroy, where every person had outlined the duties they had toward God, relationships between family members, and the tasks involved in running a household. It served to reinforce obedience and submission to God, the Tsar, and the Russian Orthodox Church. A quote from its text, “A wife should ask her husband every day about matters of piety, so she will know how to save her soul, please her husband, and structure her house well. She must obey her husband in everything.” Not so dissimilar to the King James Bible where it states in Ephesians 5:24, “Now as the church submits to Christ, so also wives should submit in everything to their husbands.” Key obligations of people living in this era were, but not limited to, fasting, prayer, icon worship, and the giving of donations.

Societies were governed by way of autocracy, guided mainly by male dominance and Patriarchalism, with absolute control over people in all their daily affairs. They used religion to justify their authority and declared that as Kings, and sometimes Queens, that they had a divine right from God to rule absolutely. There were harsh punishments devised and often invented by bishops and priests to be used on any dissenters or people deemed as behaving or thinking outside the expected theological construction of human behavior. Executions of people, generally the common people or peasantry were usually done in public, torture was done in secret underground dungeons, in some instances if a woman violated her oath of celibacy or was accused of deceiving her husband she was buried alive. People were strapped to racks while their bones and limbs were dislocated from their bodies, and for a person with an alleged opinion differing from religious dogma, otherwise known as a heretic, the Cradle of Judas was used to hang a person naked over a spike until they usually bled to death.

Superstition was rampant under command of the Roman Catholics when the Würzburg witch trials took place in Germany from 1625 to 1631. Around 1,276 people were executed in various ways on charges of suspicion of being witches. On a global scale, between the years 1400 to 1782 (though exact figures cannot be known) but some estimate anywhere between 40,000 to 60,000 people to 3 to 4 million people were killed due to suspicion that they were a witch. Why? It may have been based on competition between the Catholic and Protestant churches for religious market share over the populations and to attract the loyalty of undecided Christians (source). A notable supposed witch was Katharina Henot, who in 1627 was tortured and burned alive after she was accused of being a witch, simply because a nun in a local convent was acting distressed.

It was the Enlightenment era that challenged the supremacy of religion and the divine right of royalty in the political and social life of Europe and abroad. It influenced the western world to develop ideas around universal human rights. The scientific method, or knowledge based upon reason, was the key ingredient in the power by which people began to understand the universe, nature, and improve their social conditions. Most importantly, the scientific method was also the basis for further establishing a judicial system on the presumption of innocence based on a secular non-religious foundation where as we know today, that a person is innocent until proven guilty. But we will never know how many people lived their lives pretending to be religious and devoted to all the insane aspects of their society, but they certainly knew what happened if they didn’t, especially women.

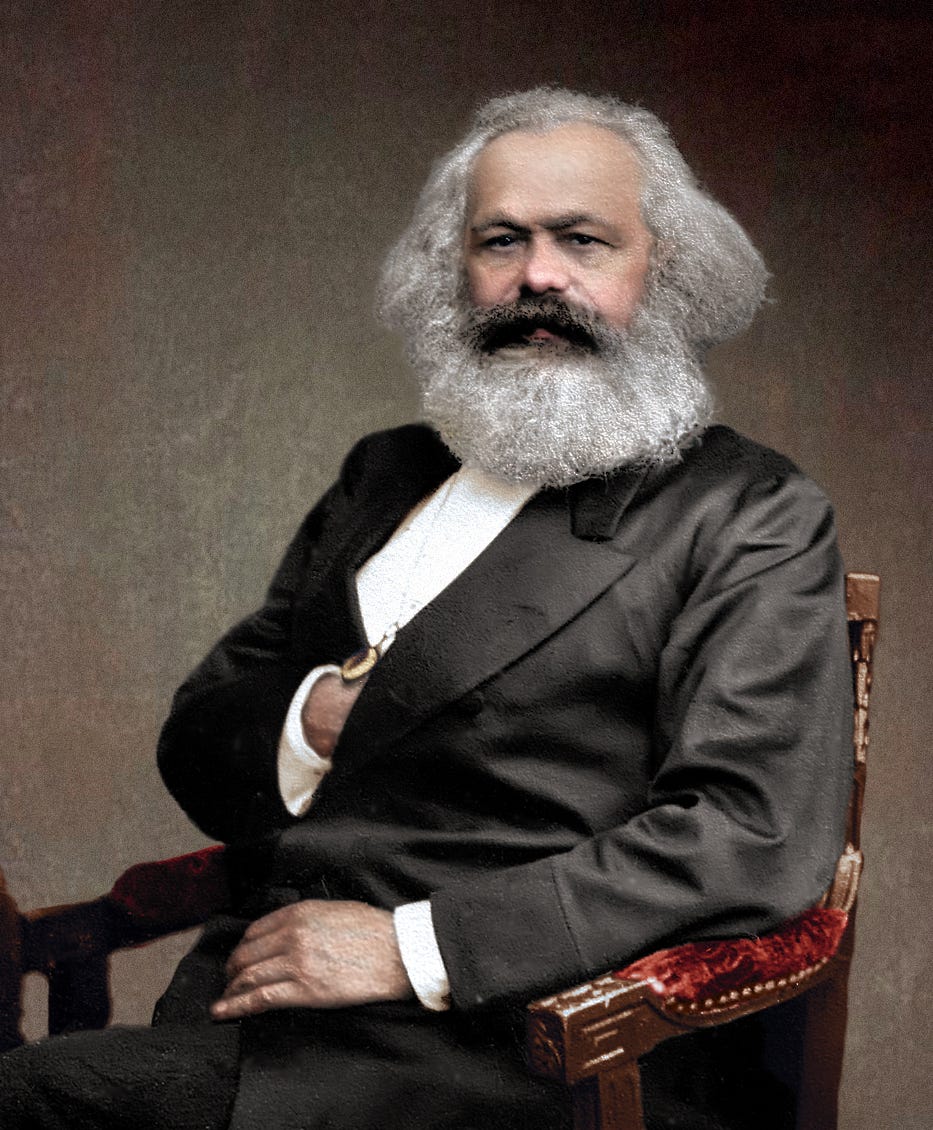

The second significant era in history that caused great change was a philosopher by the name of Karl Marx (1818 -1883). He was born in Germany at the tail end of the Enlightenment period and through the course of his life he immersed himself in all the prominent literary works of philosophy of that period. He graduated college with a degree in philosophy, writing his thesis on the Greek philosopher Epicurus. He would later be the head editor of a pro-democracy publication known as the Rheinische Zeitung writing in opposition to the King of Prussia. He was a foreign correspondent for the New-York Daily Tribune writing articles on current affairs in Europe for an American audience.

In 1848 Marx published his most influential work, the Manifesto of the Communist Party. The seminal opening paragraph, “The history of all hitherto existing society (recorded history) is the history of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another… a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.” This book disseminated throughout Europe like wildfire and later into the hands of working people in America. In the United States, much of the population consisted of immigrants having strong connections to their former countries in Europe. At the time, this work vividly described the realities that people were living through, their working conditions, and gave great insight into the exact nature of the systems they worked under and how it was all created. In summary, it was a culmination of economics, history, politics, and science and synthesized the ideas behind current and prior social struggles into one body of work. It cultivated an awareness to people how there were people operating as capitalists at the top of the social hierarchy, living not from wages but from accumulated wealth and a working class at the bottom that lived from wages serving capitalists interests. This inspired new labor unions to form, social reforms, and many new social movements in anarchism, communism, and socialism during the 1800s up to the present day.

From abroad, Marx greatly admired the American revolution and the United States constitution. He was fiercely anti-slavery and was in full support of the Union army during the Civil War in America. This may have been why he had a connection (at least through letters) to Abraham Lincoln. It is debated whether or not Lincoln was deeply influenced by Marx as there is noticeable changes in topics that Lincoln began to discuss in speeches during this time with greater attention to anti-slavery and more emphasis on the nature of capital, labor, and the working class, “labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration” (Source).

Marx was also highly critical of organized religion. He often wrote about it in his works and wove it in with his writings on economics. He made the parallel between the accumulation of wealth and religious control. A popular quote in context from one of his works,

“Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people. The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo. Criticism has plucked the imaginary flowers on the chain not in order that man shall continue to bear that chain without fantasy or consolation, but so that he shall throw off the chain and pluck the living flower. The criticism of religion disillusions man, so that he will think, act, and fashion his reality like a man who has discarded his illusions and regained his senses, so that he will move around himself as his own true Sun. Religion is only the illusory Sun which revolves around man as long as he does not revolve around himself.” - Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Karl Marx, 1843

Philosophers, scientists, and public intellectuals of this period circulated their ideas through meetings at academic institutions, lodges, literary salons, coffeehouses and in printed books, journals, and pamphlets. In America, there has been a great tradition of intellectualism and radicalism. Many people of which, have had their identities removed from the timeline of generally taught history and others who get a glossing over with much of their life events left in the dark. Here are a few great Americans that I hope you know already, but if not, I hope you will take note and go and learn more about them on your own in your free time.

Thomas Paine (1737 - 1809)

“I shall, in the progress of this work, declare the things I do not believe, and my reasons for not believing them. I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church. All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian or Turkish, appear to me no other than human inventions, set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit. I do not mean by this declaration to condemn those who believe otherwise; they have the same right to their belief as I have to mine. But it is necessary to the happiness of man, that he be mentally faithful to himself. Infidelity does not consist in believing, or in disbelieving; it consists in professing to believe what he does not believe.” - Age of Reason, 1794

Born February 9th, 1737 in Thetford, England, the radical Thomas Paine at the age of 37 was given a connection to Benjamin Franklin through his English friend George Lewis Scott, a mathematician and tutor to the future King George III and was also the commissioner of excise. It is thought that this connection was made because Paine had written The Case of the Officers of Excise, printed in England in 1772 exposing corruption in the British Excise Service (source). At the time, Paine was dealing with marital and financial issues and desired to travel to the American colonies and so Franklin wrote a letter of reference to his son-in-law Richard Bache, the husband of Franklins daughter Sarah Franklin Bache, requesting that he sponsor Paine and host him until he got on his feet in the colonies.

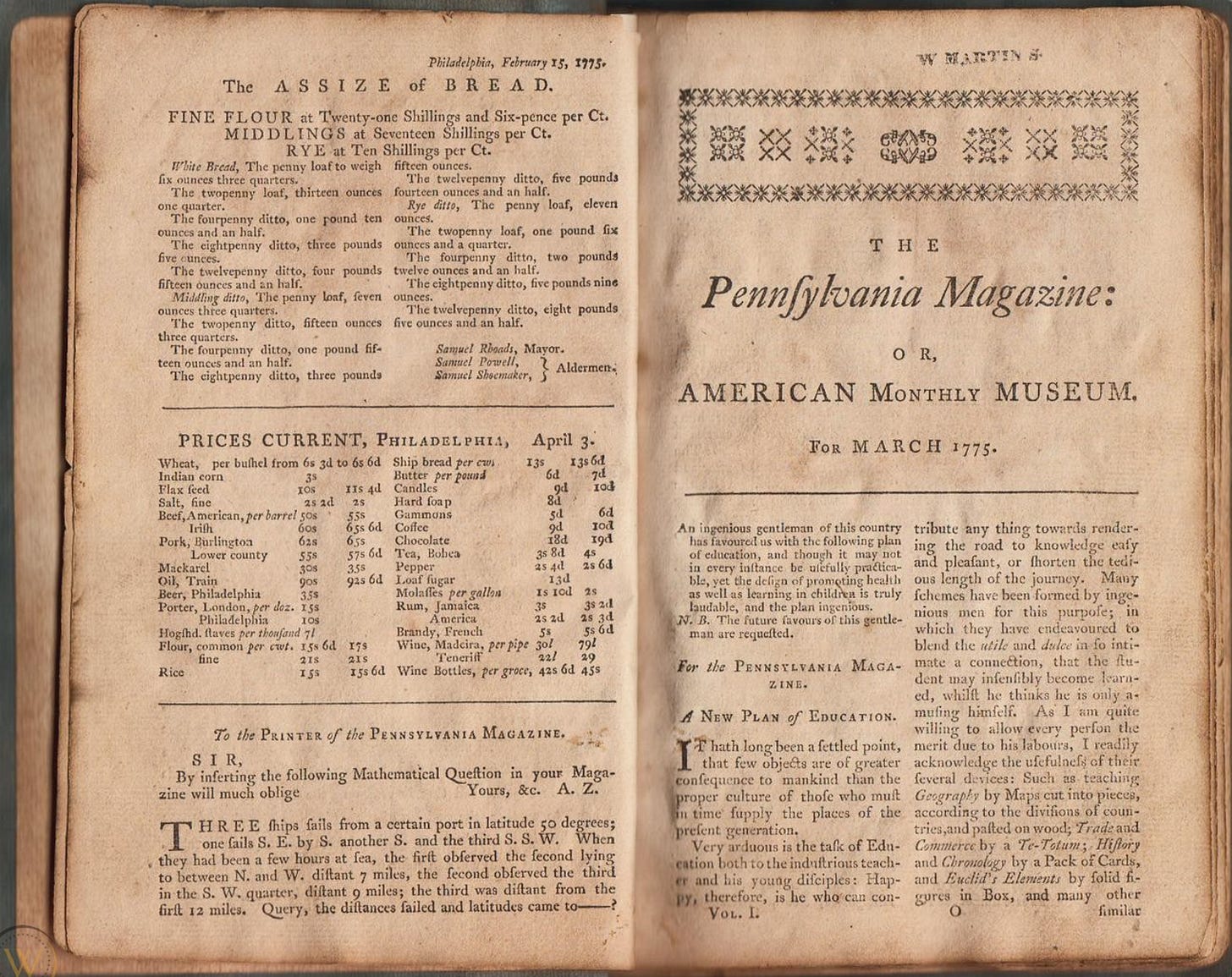

Paine came to the British American colonies in late November of 1774 to live in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He arrived at a time when Philadelphia had a population of at least 30,000 people and thousands of new settlers were beginning to arrive annually in search of fortunes and opportunity. It was the most populated city in the colonies and attracted the most diverse interests in the arts, commerce, invention, and the sciences of the time. He took a job as an editor for the Pennsylvania Magazine, often signing his work with pseudonyms like Aesop, Atlanticus, Vox Populi, or Humanus. His political writings probably gained him social status in the city, making connections with people like George Washington, James Monroe, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson. His writings contained fierce commentary on the nature of British monarchy and its tyranny over people from far away. He was greatly influenced by the enlightenment philosophers of Europe like John Locke, Rousseau, and the critical writings on reason, Christianity, and slavery by Voltaire. Paine opposed slavery and was one of the earliest advocates of social security, universal free public education, and a guaranteed minimum income by means of direct federal funding and taxes on inherited property. He was also an inventor patenting an iron bridge in England, attempted to create a smokeless candle, and worked with John Fitch from Windsor, Connecticut on the early development of steam engines.

There were aggravations and conflicts happening between the colonies and the British Empire and King George III over issues with taxation, but for Paine, he argued that they should go further and fight for independence (a timeline leading up to the American Revolution). This is when he wrote one of the most famous writings in American history known as Common Sense, published anonymously on January 10th, 1776. It was a 47 page pamphlet that in a few months time sold thousands of copies. It caused such commotion that by April 12th, 1776, North Carolina cast the first official vote for independence from Britain with the Halifax Resolves.

In 1777, initially unknown to him Paine was appointed by Congress unanimously as the first secretary to the Committee for Foreign Affairs. But not long after, he exposed a corrupt financial dealing, embezzlement through arms sales from France by Silas Deane, a native of Groton, Connecticut and member of the Continental Congress working as a secret agent in France. Paine felt he credibly found Deane personally profiting from French aid to the United States and began publishing evidence anonymously. But by revealing confidential information, Paine was let go from his position in 1779.

His ideas and writings did not stop with the American revolution. He went against religious power and political order, strongly defending freedom of speech and freedom of the press. He wrote Age of Reason in 1794 as a sort of activist, completely dissecting the Bible and exposing flagrant corruption within the Christian church. Founding fathers such as Benjamin Franklin, the man arguably responsible for Paine’s success in America, wrote to him stating to “burn” his writing before publishing it as it was too radical for its time. Years later, it was noted that an American President, Theodore Roosevelt had either said or written (I’ve yet to find the exact source) that Thomas Paine was a “dirty little atheist” in an effort to discredit him and further exile him from public historical awareness. To be clear, Thomas Paine was not an atheist. He wrote a remarkable degree on the topic of his belief system that it is rather absurd and disingenuous for anyone who has read his work to claim he lacked belief in the existence of God. He declared himself a Deist, expressing the belief in an ever-present God that reveals itself through nature and understandable through great observation, the sciences, and drawing connections and parallels through critical thinking and reason. In his own words, ironically reversing atheism onto religion itself,

“As to the Christian system of faith, it appears to me as a species of Atheism – a sort of religious denial of God. It professes to believe in a man rather than in God. It is a compound made up chiefly of Manism with but little Deism… The effect of this obscurity has been that of turning everything upside down, and representing it in reverse, and among the revolutions it has thus magically produced, it has made a revolution in theology. That which is now called natural philosophy, embracing the whole circle of science, of which astronomy occupies the chief place, is the study of the works of God, and of the power and wisdom of God in his works, and is the true theology… It is not the study of God himself in the works that he has made, but in the works or writings that man has made; and it is not among the least of the mischiefs that the Christian system has done to the world, that it has abandoned the original and beautiful system of theology, like a beautiful innocent, to distress and reproach, to make room for the hag of superstition.” - Age of Reason, 1794

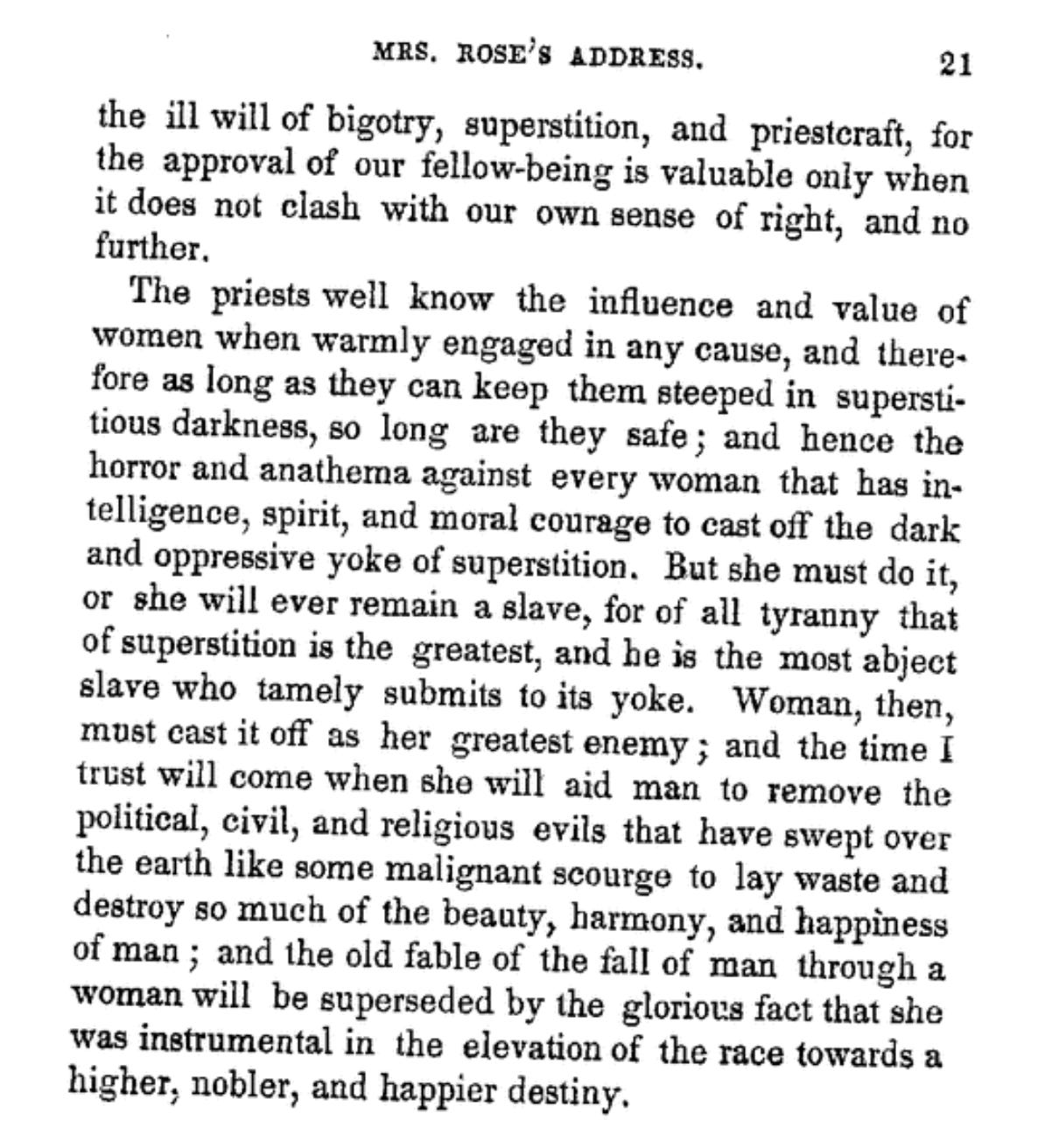

Ernestine Rose (1810 - 1892)

At the age of 26, the radical Ernestine Rose emigrated to the US and settled in New York City around 1837 until 1869. She was anti-slavery, atheist, immigrant, feminist, a freethinker, sobriety advocate, socialist, suffragist, trade unionist, and a women’s rights activist. She spoke Polish, as she was born in Piotrków, Poland but she had traveled much of Europe learning and speaking many languages. This would become valuable in the US when she gave lectures to immigrant working class populations at the time. Prior to living in the US, she lived in England, befriending the famous Robert Owen in 1832 - the founder of what is known as utopian socialism. The two formed a close bond, giving lectures every week and forming various workers organizations. It was here where she began her career as a lecturer in socialist circles and met her husband William Rose.

She traveled by rail and stagecoach to more than 23 US states, speaking in churches, barns, halls, and state legislatures. Rose refused to accept any fee for her public appearances and insisted on paying her own traveling expenses, paying for their expenses by way of her and her husbands small businesses out of their home in New York City (source). Rose favored debating points of differences with other people and reformers as she believed this was the way to reach truth. She was a regular speaker at the annual January 29th Thomas Paine Dinner in New York, speaking about anti-slavery, women’s rights, and freethought ideas and by 1853, she become the first woman president of that organization.

It has to be noted that for her time, her ideas were simply too innovative, considered outlandish, and too challenging for sustained acceptance. Though she was critically acclaimed among many leftists and reformers at the time, at one point considered the most famed women rights advocates in the country, she was often banished to the margins for her beliefs and admirable convictions. Hence why she is still very much forgotten to this day.

“To achieve this glorious victory of right over might, woman has much to do. Man may remove her legal shackles, and recognize her as his equal, which will greatly aid in her elevation; but the law cannot compel her to cultivate her mind and take an independent stand as a free being. She must cast off that mountain weight, that intimidating cowardly question, which like a nightmare presses down all her energies, namely, "What will people say? What will Mrs. Grundy say?" Away with such slavish fears! Woman must think for herself, and use for herself that greatest of all prerogatives - judgment of right and wrong. And next she must act according to her best convictions, irrespective of any other voice than that or right and duty. The time, I trust, will come, though slowly, yet surely, when woman will occupy that high and lofty position, for which nature has so eminently fitted her, in the destinies of humanity.”

- Speech at the National Woman's Rights Convention, Oct. 15th, 1851, Worcester, Massachusetts Source

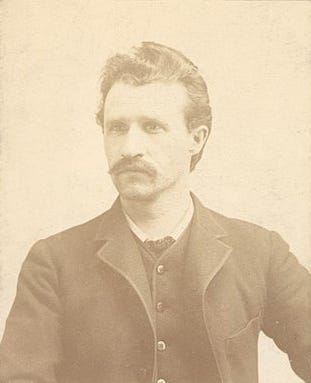

August Spies (1855 - 1887)

“Anarchism does not mean bloodshed, does not mean robbery, arson, etc. Anarchism means peace and tranquility to all. Anarchism, or Socialism, means the reorganization of society upon scientific principles and the abolition of causes which produce vice and crime. Capitalism first produces these social diseases and then seeks to cure them by punishment.” - Statements of the Accused, August Spies, 1886

In an autobiographical sketch, “My name is August Vincent Theodore Spies, (pronounced Spees). I was born within the ruins of the old robbers castle Landeck, upon a high mountain’s peak (Landeckerberg), Central Germany, December 10th, 1855. My father was a forester, the forest house was a government building, and served—only in a different form—the same purposes the old castle had served several centuries before. The noble Knight-hood of highway robbery, the traces of which were still discernable in the remnants of the old castle… Yes, the people in these villages toiled all their lives from early dawn till late at night to fill the vaults of those noble knights, who in return had the kindness to maintain ‘peace and order’ for them. Par example: if one of these toiling peasants expressed his dissatisfaction of the existing order of things, if he complained of the heavy and unbearable tasks placed upon him, ‘law and order’ demanded that he be placed upon one of the racks you have seen a relic of, to be tortured into obedience and submission… Many of these peasants were put to an ignominious death. Some of them would persist in their folly that it could not be the object of society nor the intention of Providence to have a thousand good people kill themselves in a laborious life for the glory, enrichment and grandeur of a few ungrateful, vicious wretches. Dangerous teachings were a menace to society, and their promulgators were unceremoniously stamped out… My philosophy has always been that the object of life can only consist in the enjoyment of life, and that the rational application of this principle is true morality.”

Spies emigrated to the United States and settled in Chicago, Illinois in 1872. By 1875 he became interested in leftist politics of that day and by 1880 was a leader in the Chicago school of anarchism. By 1884 he became the editor of the radical newspaper Arbeiter Zeitung which was founded after the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. The midwest at that time was dominated by socialist parties and other leftist organizations based on anarchism and communism. For the anarchist, they believed that each person had their own mind and ideals, desiring to live co-operatively among their peers with constant support and social improvement. They often favored no laws issued by the state and no accumulation of capital by a wealthy few. They avidly discoursed the idea of private property, believing it to be a concept based on a system of slavery and that private property was only acquired by a form of theft by an elite class. The anarchists are were often staunchly atheist as they perceived the creation of religion as manmade and its doctrines were used to subordinate people into submission by creating social classes and ranks.

At that time, the work day could range from at least 10 to 16 hours and sometimes more. The work week was typically six days a week and the use of child labor was common. A federal report states that the average wages of women in textile factories from 1833-1850 was $2 a week (source). The International Workingmen's Association, a leftist organization founded in London established the modern construct of how people should be treated as workers and the age for which was suitable to become a worker. As it stated, “A preliminary condition, without which all further attempts at improvement and emancipation must prove abortive, is the limitation of the working day. It is needed to restore the health and physical energies of the working class, that is, the great body of every nation, as well as to secure them the possibility of intellectual development, sociable intercourse, social and political action. We propose 8 hours work as the legal limit of the working day… By adult persons we understand all persons having reached or passed the age of 18 years.”

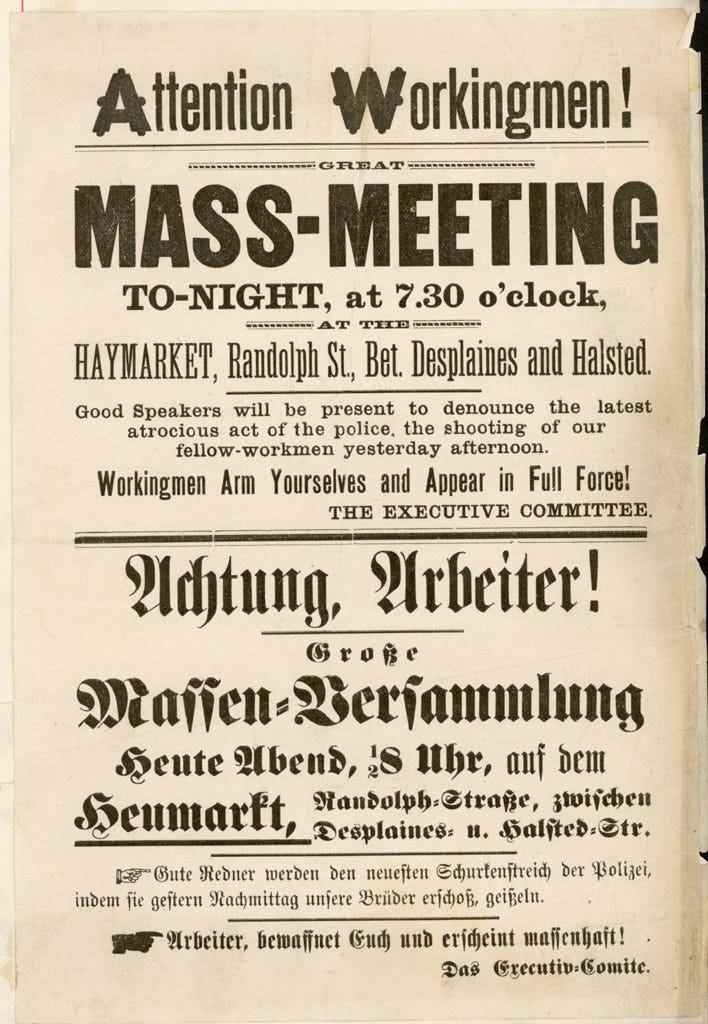

On Saturday May 1st, 1886 (now a national public holiday in many countries across the world) a strike began throughout the United States in support of an eight-hour work day. Over the next few days between 300,000 and 500,000 men and women refused to go to work. In Chicago, over 40,000 people were on strike against their employers. Police forces alongside the US Army and National Guard were dispersed everywhere, often violently antagonizing and beating workers, and trying to get them to go back to work. Many speeches were held from podiums, preaching to the workers out on strike. This event is known as the Haymarket Affair. However, on the night of May 4th, August Spies was one of the many to give a lecture to the crowds, when not long after, a bomb filled with dynamite exploded killing seven policemen with around 60 policemen wounded, and at least four workers died. The next morning, Spies was arrested along with several other known leftists and put in jail. He spent months attempting to appeal his case as he was most certainly innocent of the crime. Due to his affiliations with leftist organizations, he was one of several people singled out and accused for the crime. His case went up to the Illinois Supreme Court (Spies v. Illinois) where they determined that speech and printed materials constituted enough evidence to be held criminally responsible for the death and violence that day. Eight anarchists and socialists were indicted for the incident and all but one sentenced to death.

In his last court appearance, he gave an address to the judge before being sentenced to death. August Spies said this,

“But, if you think that by hanging us you can stamp out the labor movement—the movement from which the downtrodden millions, the millions who toil and live in want and misery, the wage slaves, expect salvation—if this is your opinion, then hang us! Here you will tread upon a spark, but here, and there, and behind you, and in front of you, and everywhere, flames will blaze up. It is a subterranean fire. You cannot put it out. The ground is on fire upon which you stand. You can't understand it. You don't believe in magical arts, as your grandfathers did, who burned witches at the stake, but you do believe in conspiracies, you believe that all these occurrences of late are the work of conspirators! You resemble the child that is looking for his picture behind the mirror. What you see, and what you try to grasp is nothing but the deceptive reflex of the stings of your bad conscience. You want to "stamp out the conspirators"—the "agitators?" Ah, stamp out every factory lord who has grown wealthy upon the unpaid labor of his employees. Stamp out every landlord who has amassed fortunes from the rent of overburdened workingmen and farmers. Stamp out every machine that is revolutionizing industry and agriculture, that intensifies the production, ruins the producer, that increases the national wealth, while the creator of all these things stands amidst them tantalized with hunger! Stamp out the railroads, the telegraph, the telephone, steam and yourselves—for everything breathes the revolutionary spirit.”

The US government sentenced Spies to death by hanging on November 11th, 1887. His last words standing from the gallows moments before being hung were, “the day will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today.”

The May Day Strikes helped convince United States President Grover Cleveland to implement Labor Day, signing bill S. 730 on June 28th, 1894 establishing Labor Day as a national holiday, a holiday that celebrates the American worker. On May 19th, 1869 President Ulysses S. Grant issued a National Eight Hour Law Proclamation. A film showing a Labor Day Parade in 1906 in Fitchburg, Massachusetts can be seen here.